| Wilberforce |

W i l l i a m W i l b e r f o r c e

Statesman Extraordinaire

William Wilberforce was born in Kingston Upon

Hull on

August 24,1759, the only son of Robert Wilberforce (1728–68), a wealthy

merchant, and his wife Elizabeth. His grandfather William (1690–1776) had made

the family fortune in the maritime trade with Baltic countries, and had twice

been elected mayor of Hull.

Wilberforce was a small, sickly and

delicate child, with poor eyesight. In 1767 he began attending Hull Grammar

School, at the time headed by a young, dynamic headmaster, Joseph

Milner who was to become a life-long

friend. Wilberforce profited from the supportive atmosphere at the school until

the death of his father in 1768.

He spent his holidays in Wimbledon,

where he grew extremely fond of his relatives. He became interested in evangelical

Christianity because of their influence, especially that of his aunt Hannah,

sister of the wealthy Christian merchant John Thornton and a supporter of the

leading Methodist preacher George Whitefield.

Wilberforce's staunchly Church of

England mother and grandfather, alarmed at these nonconformist influences and

at his leanings towards evangelicalism, brought the 12-year-old boy back to

Hull in 1771. Influenced by Methodist scruples, he initially resisted Hull's

lively social life, but as his religious fervor diminished, he embraced

theatre-going, attended balls and played cards.

In October 1776 at the age of

seventeen, Wilberforce went up to St. John’s

College,

Cambridge. The deaths of his

grandfather and uncle in 1776 and 1777 respectively had left him independently

wealthy, and as a result he had little inclination or need to apply himself to

serious study. Instead, he immersed himself in the social round of student

life, and pursued a hedonistic lifestyle enjoying cards, gambling and

late-night drinking sessions–although he found the excesses of some of his

fellow students distasteful. Witty, generous, and an excellent

conversationalist, Wilberforce was a popular figure. He made many friends,

including the more studious future prime minister, William Pitt.

Wilberforce began to consider a

political career while still at university, and during the winter of 1779–80 he

and Pitt frequently watched House of Commons debates from the gallery. Pitt,

already set on a political career, encouraged Wilberforce to join him in

obtaining a parliamentary seat. In September 1780, at the age of twenty-one and

while still a student, Wilberforce was elected Member of Parliament (MP) for Kingston Upon

Hull, spending over £8,000 to ensure he

received the necessary votes, as was the custom of the time.

Free from financial pressures, Wilberforce sat as an independent, resolving to be "no party man". Criticized at times for inconsistency, he supported both Tory and Whig governments according to his conscience, working closely with the party in power, and voting on specific measures according to their merits. Wilberforce attended Parliament regularly, but he also maintained a lively social life, becoming an habitué of gentlemens’ gambling clubs.

The writer and socialite, Madame de Stael, described him as the "wittiest man in England" and, according to Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, the Prince of Wales [future king of England] said that he would go anywhere to hear Wilberforce sing. Wilberforce used his speaking voice to great effect in political speeches; the diarist and author, James Boswell, witnessed Wilberforce's eloquence in the House of Commons and noted: "I saw what seemed a mere shrimp mount upon the table; but as I listened, he grew, and grew, until the shrimp became a whale."

During the frequent government changes of 1781–84 Wilberforce supported his friend Pitt in parliamentary debates, and in autumn 1783 Pitt, Wilberforce and Edward Elliot (later to become Pitt's brother-in-law), traveled to France for a six-week holiday together. After a difficult start in Rheims, where their presence aroused police suspicion that they were English spies, they visited Paris, meeting Benjamin Franklin, Lafayette, Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, and joined the French court at Fontainebleau.

Pitt became Prime Minister in

December 1783, with Wilberforce a key supporter of his minority

government. Despite their close friendship,

there is no record that Pitt offered Wilberforce a ministerial position in this

or future governments. This may have been due to Wilberforce's wish to remain

an independent MP. Alternatively, Wilberforce's frequent tardiness and

disorganization, as well as the chronic eye problems that at times made reading

impossible, may have convinced Pitt that his trusted friend was not ministerial

material.

In October 1784, Wilberforce

embarked upon a tour of Europe which would change his life and ultimately his

future career. He travelled with his mother and sister in the company of Isaac

Milner, the brilliant younger brother of his former headmaster. They visited

the French Riviera and enjoyed the usual pastimes of dinners, cards, and

gambling.

In February 1785, Wilberforce

returned to the United Kingdom temporarily, to support Pitt’s proposals for

parliamentary reforms. He rejoined the party in Genoa, Italy, from where they

continued their tour to Switzerland. Milner accompanied Wilberforce to England,

and on the journey they read The Rise and Progress of Religion in the Soul

by Philip Doddridge,

a leading early 18th-century English non-conformist.

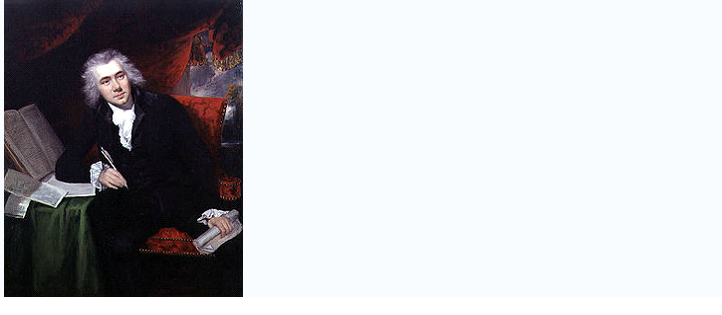

William Wilberforce by John Rising, 1790, pictured at the age of 29

Wilberforce's spiritual journey is

thought to have begun at this time. He started to rise early to read the Bible and

pray and kept a private journal. He underwent an evangelical conversion, regretting his past life and resolving to commit his

future life and work to the service of God.

His conversion changed some of his habits but not his nature: he remained outwardly cheerful, interested, and respectful, tactfully urging others towards his new faith. Inwardly, he underwent an agonizing struggle and became relentlessly self-critical, harshly judging his spirituality, use of time, vanity, self-control, and relationships with others.

At the time religious enthusiasm was generally regarded as a social transgression and was stigmatized in polite society. Evangelicals in the upper classes, such as Sir Richard Hill, the Methodist MP for Shropshire, and Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, were exposed to contempt and ridicule, and Wilberforce's conversion led him to question whether he should remain in public life.

Wilberforce sought guidance from

John

Newton, a leading Evangelical Anglican

clergyman of the day and Rector of St.

Mary Woolnoth in the City of London. [John

Newton is the former libertine and slave ship captain, profoundly

converted to Christ, and who wrote “Amazing Grace.”] Both

Newton and Pitt counseled Wilberforce to remain in politics, and he resolved to

do so "with increased diligence and conscientiousness". Thereafter,

his political views were informed by his faith and by his desire to promote

Christianity and Christian ethics in private and public life.

His views were often deeply

conservative, opposed to radical changes in a God-given political and social

order, and focused on issues such as the observance of the Sabbath and the

eradication of immorality through education and reform. As a result, he was

often distrusted by progressive voices due to his conservatism, and regarded

with suspicion by many Tories who saw Evangelicals as radicals, bent on the

overthrow of church and state.

The British had initially become involved in the slave trade during the 16th century. By 1783, the triangular route that took British-made goods to Africa to buy slaves, transported the enslaved to the West Indies, and then brought slave-grown products such as sugar, tobacco, and cotton to Britain, represented about 80 per cent of Great Britain's foreign income. British ships dominated the trade, supplying French, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese and British colonies, and in peak years carried forty thousand enslaved men, women and children across the Atlantic in the horrific conditions of the middle passage. Of the estimated 11 million Africans transported into slavery, about 1.4 million died during the voyage.

The British campaign to abolish the slave trade is generally considered to have begun in the 1780s with the establishment of the Quakers' antislavery committees, and their presentation to Parliament of the first slave trade petition in 1783. The same year, Wilberforce, while dining with his old Cambridge friend Gerard Edwards, met Rev. James Ramsey, a ship’s surgeon who had become a clergyman on the island of St Christopher (later St. Kitts) in the Leeward Islands and a medical supervisor of the plantations there. What Ramsay had witnessed of the conditions endured by the slaves, both at sea and on the plantations, horrified him.

an essay on

the treatment and conversion of African slaves in the British sugar colonies,

which was highly critical of slavery in the West Indies. The book, published in

1784, was to have an important impact in raising public awareness and interest,

and it excited the ire of West Indian planters who in the coming years attacked

both Ramsay and his ideas in a series of pro-slavery tracts.

Wilberforce apparently did not

follow up on his meeting with Ramsay. However, three years later, and inspired

by his new faith, Wilberforce was growing interested in humanitarian reform. In

November 1786 he received a letter from Sir Charles Middleton that re-opened

his interest in the slave trade. At the urging of Lady Middleton, Sir Charles

suggested that Wilberforce bring forward the abolition of the slave trade in

Parliament. Wilberforce responded that "he felt the great importance of

the subject, and thought himself unequal to the task allotted to him, but yet

would not positively decline it". He began to read widely on the subject,

and met with others who were like-minded.

In early 1787, Thomas Clarkson, a

fellow graduate of St John's, Cambridge, who had become convinced of the need

to end the slave trade after writing a prize-winning essay on the subject while

at Cambridge, called upon Wilberforce at Old Palace Yard with a published copy

of the work. This was the first time the two men had met; their collaboration

would last nearly fifty years. Clarkson began to visit Wilberforce on a weekly

basis, bringing first-hand evidence he

had obtained about the slave trade. The Quakers, already working for abolition,

also recognized the need for influence within Parliament, and urged Clarkson to

secure a commitment from Wilberforce to bring forward the case for abolition in

the House of Commons.

Commitment at the dinner party:

It was arranged that Bennet Langton, a Lincolnshire landowner and mutual acquaintance of Wilberforce and Clarkson, would organize a dinner party in order to ask Wilberforce formally to lead the parliamentary campaign. The dinner took place on March 13, 1787; other guests included Charles Middleton, Sir Joshua Reynolds, William Windham, MP, James Boswell and Isaac Hawkins Browne, MP. By the end of the evening, Wilberforce had agreed in general terms that he would bring forward the abolition of the slave trade in Parliament, "provided that no person more proper could be found."

The same spring, on May 12, 1787,

the still hesitant Wilberforce held a conversation with William Pitt and the

future Prime Minister William Grenville as they sat under a large oak tree on

Pitt's estate in Kent. Under what came to be known as the "Wilberforce

Oak" at Holwood, Pitt challenged his friend: "Wilberforce, why don’t

you give notice of a motion on the subject of the Slave Trade? You have already

taken great pains to collect evidence, and are therefore fully entitled to the

credit which doing so will ensure you. Do not lose time, or the ground will be

occupied by another." Wilberforce’s response is not recorded, but he later

declared in old age that he could "distinctly remember the very knoll on

which I was sitting near Pitt and Grenville" where he made his decision.

Wilberforce's

involvement in the abolition movement was motivated by a desire to put his

Christian principles into action and to serve God in public life. He and other

Evangelicals were horrified by what they perceived was a depraved and

unchristian trade, and the greed and avarice of the owners and traders.

Wilberforce sensed a call from God, writing in a journal entry in 1787 that

"God Almighty has set before me two great objects, the suppression of the

Slave Trade and the Reformation of Manners [moral values]". The conspicuous

involvement of Evangelicals in the highly popular anti-slavery movement served

to improve the status of a group otherwise associated with the less popular

campaigns against vice and immorality.

On May 22, 1787, the first meeting of the Society for Affecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade took place, bringing like-minded British Quakers and Anglicans together in the same organization for the first time. The committee chose to campaign against the slave trade rather than slavery itself, with many members believing that slavery would eventually disappear as a natural consequence of the abolition of the trade. Wilberforce, though involved informally, did not join the committee officially until 1791.

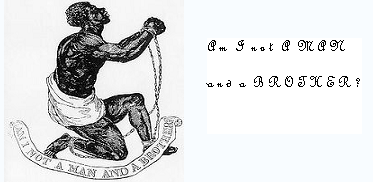

The society was highly successful in raising public awareness and support, and local chapters sprang up throughout Great Britain. Clarkson travelled the country researching and collecting first-hand testimony and statistics, while the committee promoted the campaign, pioneering techniques such as lobbying, writing pamphlets, holding public meetings, gaining press attention, organizing boycotts and even using a campaign logo: an image of a kneeling slave above the motto "Am I not a Man and a Brother?" designed by the renowned pottery-maker Josiah Wedgwood.

The committee also sought to influence

slave-trading nations such as France, Spain, Portugal, Denmark, Holland and the

United States, corresponding with anti-slavery activists in other countries and

organizing the translation of English-language books and pamphlets. These included books by former slaves Ottogah

Cugoando and Oluado Equiano, who had published influential works on slavery and the

slave trade in 1787 and 1789 respectively.

They and other free blacks,

collectively known as "Sons of Africa", spoke at debating societies

and wrote spirited letters to newspapers, periodicals and prominent figures, as

well as public letters of support to campaign allies.

Hundreds of parliamentary petitions opposing the slave trade were received in 1788 and following years, with hundreds of thousands of signatories in total.

The campaign proved to be the world's first grassroots human rights campaign, in which men and women from different social classes and backgrounds volunteered to end the injustices suffered by others.

Wilberforce had planned to introduce

a motion giving notice that he would bring forward a bill for the Abolition of

the Slave Trade during the 1789 parliamentary session. However, in January 1788

he was taken ill with a probable stress-related condition, now thought to be ulcerative

colitis was several months before he was able to resume work. His regular bouts

of gastrointestinal illnesses precipitated the use of moderate quantities of

opium, which proved effective in alleviating his condition, and

which he continued to use for the rest of his life.

During Wilberforce's absence, Pitt, who had long been supportive of abolition, introduced the preparatory motion himself, and ordered a Privy Council investigation into the slave trade, followed by a House of Commons review. With the publication of the Privy Council report in April 1789 and following months of planning, Wilberforce commenced his parliamentary campaign.

On May 12, 1789, he made his

first major speech on the subject of abolition in the House of Commons, in

which he reasoned that the trade was morally reprehensible and an issue of

natural justice. Drawing on Thomas Clarkson's mass of evidence, he described in

detail the appalling conditions in which slaves travelled from Africa in the middle

passage, and argued that abolishing the trade would also bring an improvement

to the conditions of existing slaves in the West Indies.

He moved twelve resolutions condemning the slave trade,

but made no reference to the abolition of slavery itself, instead dwelling on

the potential for reproduction in the existing slave population should the

trade be abolished.

With the tide running against them,

the opponents of abolition delayed the vote by proposing that the House of

Commons hear its own evidence, and Wilberforce, in a move that has subsequently

been criticized for prolonging the slave trade, reluctantly agreed.

The

hearings were not completed by the end of the parliamentary session, and were deferred until the following year. In the

meantime, Wilberforce and Clarkson tried unsuccessfully to take advantage of

the egalitarian atmosphere of the French

Revolution to press for France's abolition of the trade, which was, in

any event, to be abolished in 1794 as a result of the bloody slave revolt in St.

Dominque (later to be known as

Haiti),

although later briefly restored by Napoleon in 1802.

In January 1790, Wilberforce

succeeded in speeding up the hearings by gaining approval for a smaller

parliamentary select committee to consider the vast quantity of evidence which

had been accumulated. Wilberforce's house in Old Palace Yard became a center

for the abolitionists' campaign, and a focus for many strategy meetings.

Petitioners for other causes also besieged him there, and his ante-room

thronged from an early hour, like "Noah's Ark, full of beasts clean and

unclean", according to Hannah More.

Let

us not despair; it is a blessed cause, and success, ere long,

will crown our

exertions.

Already

we have gained one victory;

we have obtained, for these poor creatures,

the

recognition

which, for a while was most shamefully denied.

This

is the first fruits of our efforts;

let us persevere and our triumph will be

complete.

Never,

never will we desist till we have wiped away

this scandal from the Christian

name,

released ourselves from the load of guilt,

under which we at present labour,

and extinguished

of which our posterity,

looking back to the

history of these

will scarce believe that it has been suffered to exist so long

a

disgrace and

—William Wilberforce, speech before the House of Commons, April 18, 1791

Interrupted by a general election in June 1790, the committee finally finished hearing witnesses, and in April 1791 with a closely reasoned four-hour speech, Wilberforce introduced the first parliamentary bill to abolish the slave trade. However, after two evenings of debate, the bill was easily defeated by 163 votes to 88, the political climate having swung in a conservative direction in the wake of the French Revolution, and in reaction to an increase in radicalism and to slave revolts in the French West Indies. Such was the public hysteria of the time that even Wilberforce himself was suspected by some of being a Jacobin agitator.

This was the beginning of a

protracted parliamentary campaign, during which Wilberforce's commitment never

wavered, despite frustration and hostility. He was supported by a group holding

evangelical Christian convictions, and consequently dubbed "the

Saints."

The "Saints" were an informal community, characterized by considerable intimacy as well as a commitment to practical Christianity and an opposition to slavery. They developed a relaxed family atmosphere, wandering freely in and out of each other's homes and gardens, and discussing the many religious, social, and political topics that engaged them.

Pro-slavery advocates claimed that enslaved Africans were lesser human beings who benefited from their bondage. Wilberforce, the Clapham Sect, and others, were anxious to demonstrate that Africans, and particularly freed slaves, had human and economic abilities beyond the slave trade, and were capable of sustaining a well-ordered society, trade and cultivation. Inspired in part by the utopian vision of Granville Sharp, they became involved in the establishment in 1792 of a free colony in Sierra Leone with black settlers from the United Kingdom, Nova Scotia and Jamaica, as well as native Africans and some whites. They formed the Sierra Leone Company, with Wilberforce subscribing liberally to the project in money and time.

The

dream was of an ideal society in which races would mix on equal terms; the

reality was fraught with tension, crop failures, disease, death, war and

defections to the slave trade. Initially a commercial venture, the British

government assumed responsibility for the colony in 1808. The colony, although

troubled at times, was to become a symbol of anti-slavery in which residents,

communities, and African tribal chiefs, worked together to prevent enslavement

at the source, supported by a British naval blockade to stem the region's slave trade.

On April 2, 1792, Wilberforce

again brought a bill calling for abolition. The memorable debate that followed

drew contributions from the greatest orators in the house, William Pitt and Charles

James Fox, as well as from Wilberforce himself.

Henry Dundas, as Home Secretary, proposed a compromise solution of so-called

"gradual abolition" over a number of years. This was passed by 230 to

85 votes, but the compromise was little more than a clever ploy, with the

intention of ensuring that total abolition would be delayed indefinitely.

On February 26, 1793, another vote to abolish the slave trade was narrowly defeated by eight votes. The outbreak of war with France the same month effectively prevented any further serious consideration of the issue, as politicians concentrated on the national crisis and the threat of invasion. The same year, and again in 1794, Wilberforce unsuccessfully brought before Parliament a bill to outlaw British ships from supplying slaves to foreign colonies. He voiced his concern about the war and urged Pitt and his government to make greater efforts to end hostilities.

Wilberforce had shown little

interest in women, but in his late thirties twenty-year-old Barbara

Ann Spooner (1777–1847) was recommended by a

friend as a potential bride. Wilberforce met her two days later on April 15,

1797, and was immediately smitten; following an eight-day whirlwind romance, he

proposed. Despite the urgings of friends to slow down,

the couple married in Bath, Somerset, on May 30, 1797. They were devoted to

each other and Barbara was very attentive and supportive to Wilberforce in his

increasing ill health, though she showed little interest in his political

activities. They had six children in fewer than ten years: William (b. 1798),

Barbara (b. 1799), Elizabeth (b. 1801), Robert Isaac Wilberforce (b. 1802), Samuel

Wilberforce (b. 1805) and Henry William Wilberforce (b. 1807). Wilberforce was an indulgent and adoring father

who reveled in his time at home and at play with his offspring.

The early years of the 19th century

once again saw an increased public interest in abolition. In 1804, Clarkson

resumed his work and the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade

began meeting again, strengthened with prominent new members. In June 1804,

Wilberforce's bill to abolish the slave trade successfully passed all its

stages through the House of Commons. However, it was too late in the

parliamentary session for it to complete its passage through the House of

Lords. On its reintroduction during the 1805 session it was defeated, with even

the usually sympathetic Pitt failing to support it. On this occasion and

throughout the campaign, abolition was held back by Wilberforce's trusting,

even credulous nature, and his deferential attitude towards those in power. He

found it difficult to believe that men of rank would not do what he perceived

to be the right thing, and was reluctant to confront them when they did not.

Following Pitt's death in February 1806

Wilberforce began to collaborate more with the Whigs, especially the

abolitionists.

A radical change of tactics, which involved the introduction of a bill to ban British subjects from aiding or participating in the slave trade to the French colonies, was suggested by maritime lawyer James Stephen. It was a shrewd move since the majority of British ships were now flying American flags and supplying slaves to foreign colonies with whom Britain was at war. A bill was introduced and approved by the cabinet, and Wilberforce and other abolitionists maintained a self-imposed silence, so as not to draw any attention to the effect of the bill. The approach proved successful, and the new Foreign Slave Trade Bill was quickly passed, and received the Royal Assent on May 23, 1806. Wilberforce and Clarkson had collected a large volume of evidence against the slave trade over the previous two decades, and Wilberforce spent the latter part of 1806 writing A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, which was a comprehensive restatement of the abolitionists' case.

The death of Fox in September 1806

was a blow, and was followed quickly by a general

election in the autumn of 1806. Slavery

became an election issue, bringing more abolitionist MPs into the House of

Commons, including former military men who had personally experienced the

horrors of slavery and slave revolts. Wilberforce was re-elected as an MP for

Yorkshire, after which he returned to finishing and publishing his Letter,

in reality a 400-page book which formed the basis for the final phase of the

campaign.

Lord Grenville, the Prime Minister,

was determined to introduce an Abolition Bill in the House of Lords rather than

in the House of Commons, taking it through its greatest challenge first. When a

final vote was taken, the bill was passed in the House of Lords by a large

margin. Sensing a breakthrough that had been long anticipated, Charles Gray

moved for a second reading in the Commons on February 23, 1807. As

tributes were made to Wilberforce, whose face streamed with tears, the bill was

carried by 283 votes to 16.

Excited supporters suggested taking advantage of

the large majority to seek the abolition of slavery itself but Wilberforce made

it clear that total emancipation was not the immediate goal: "They had for

the present no object immediately before them, but that of putting stop

directly to the carrying of men in British ships to be sold as slaves."

The Slave Trade Act received the Royal Assent on March 25, 1807.

Wilberforce

was generous with his time and money, believing that those with wealth had a

duty to give a significant portion of their income to the needy. Yearly, he

gave away thousands of pounds, much of it to clergymen to distribute in their

parishes. He paid off the debts of others, supported education and missions, and

in a year of food shortages gave to charity more than his own yearly income. He

was exceptionally hospitable, and could not bear to sack any of his servants.

As a result, his home was full of old and incompetent servants kept on in charity.

Although he was often months behind in his correspondence, Wilberforce

responded to numerous requests for advice or for help in obtaining

professorships, military promotions, and livings for clergymen, or for the

reprieve of death sentences.

A supporter of the evangelical wing of the Church of England, Wilberforce believed that the revitalization of the Church and individual Christian observance would lead to a harmonious, moral society. He sought to elevate the status of religion in public and private life, making piety fashionable in both the upper- and middle-classes of society. To this end, in April,1797 Wilberforce published

A Practical View of the Prevailing

Religious System of Professed Christians in the Higher and Middle Classes of

This Country Contrasted With Real Christianity, on which he had been

working since 1793.

This was an exposition of New

Testament doctrine and teachings and a call for a revival of Christianity, as a

response to the moral decline of the nation, illustrating his own personal

testimony and the views which inspired him. The book proved to be influential

and a best-seller by the standards of the day; 7,500 copies were sold

within six months, and it was translated into several languages. Wilberforce

fostered and supported missionary activity in Britain and abroad.

Moral reform

Wilberforce's attempts to legislate

against adultery and Sunday newspapers were also in vain; his involvement and

leadership in other, less punitive, approaches were more successful in the

long-term, however. By the end of his life, British morals, manners, and sense

of social responsibility had increased, paving the way for future changes in

societal conventions and attitudes during the Victorian era.

Emancipation of enslaved Africans

The hopes of the abolitionists

notwithstanding, slavery did not wither with the end of the slave trade in the

British Empire, nor did the living conditions of the enslaved improve. The

trade continued, with few countries following suit by abolishing the trade, and

with some British ships disregarding the legislation. The Royal Navy patrolled

the Atlantic intercepting slave ships from other countries.

Wilberforce worked with the members of the African Institution to ensure the enforcement of abolition and to promote abolitionist negotiations with other countries. In particular, the US had abolished the slave trade in 1808, and Wilberforce lobbied the American government to enforce its own prohibition more strongly.

From 1816 Wilberforce introduced a

series of bills which would require the compulsory registration of slaves,

together with details of their country of origin, permitting the illegal

importation of foreign slaves to be detected. Later in the same year he began

publicly to denounce slavery itself, though he did not demand immediate

emancipation, as

"They had always thought the slaves incapable of liberty

at present, but hoped that by degrees a change might take place as the natural

result of the abolition."

As the 1820s wore on, Wilberforce

increasingly became a figurehead for the abolitionist movement, although he

continued to appear at anti-slavery meetings, welcoming visitors, and

maintaining a busy correspondence on the subject.

The year 1823 saw the founding of

the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery (later the Anti

Slavery Society, and the publication of Wilberforce's 56-page

Appeal to the

Religion, Justice and Humanity of the Inhabitants of the British Empire in

Behalf of the Negro Slaves in the West Indies.

In his treatise, Wilberforce

urged that total emancipation was morally and ethically required, and that

slavery was a national crime that must be ended by parliamentary legislation to

gradually abolish slavery. Members of Parliament did not quickly agree, and government

opposition in March 1823 stymied Wilberforce’s call for abolition. On May 15, 1823, Buxton moved another resolution

in Parliament for gradual emancipation. Subsequent debates followed in which

Wilberforce made his last speeches in the Commons, and which again saw the

emancipationists outmaneuvered by the government.

Last years

Wilberforce's health was continuing

to fail, and he suffered further illnesses in 1824 and 1825. With his family

concerned that his life was endangered, he declined a peerage and resigned his

seat in Parliament, leaving the campaign in the hands of others. Thomas

Clarkson continued to travel, visiting anti-slavery groups throughout Britain,

motivating activists and acting as an ambassador for the anti-slavery cause to

other countries, while Buxton pursued the cause of reform in Parliament. Public

meetings and petitions demanding emancipation continued, with an increasing

number supporting immediate abolition rather than the gradual approach favored

by Wilberforce, Clarkson and their colleagues.

In 1833, Wilberforce's health declined further and he suffered a severe attack of flu from which he never fully recovered. He made a final anti-slavery speech in April 1833 at a public meeting. The following month, the Whig government introduced the Bill for the Abolition of Slavery, formally saluting Wilberforce in the process. On July 26, 1833, Wilberforce heard of government concessions that guaranteed the passing of the Bill for the Abolition of Slavery. The following day he grew much weaker, and he died early on the morning of July 29.

One month later, the House of Lords passed the Slavery Abolition Act, which abolished slavery in most of the British Empire from August 1834. They voted plantation owners £20 million in compensation, giving full emancipation to children younger than six, and instituting a system of apprenticeship, requiring other enslaved peoples to work for their former masters for four to six years in the British West Indies, South Africa, Mauritius, British Honduras and Canada. Nearly 800,000 African slaves were freed, the vast majority in the Caribbean.

Leading

members of both Houses of Parliament urged that he be honored with a burial in

Westminster Abbey. The family agreed and, on August 3, 1833, Wilberforce

was buried in the north transept, close to his friend William Pitt. The funeral

was attended by many Members of Parliament, as well as by members of the

public.

While tributes were paid and Wilberforce was laid to rest, both Houses

of Parliament suspended their business as a mark of respect; a rare tribute

indeed.

[1. adapted from William Wilberforce, Wikipedia

2. In June, 2005, Lindsay House Publishing's editor visited Westminster Abbey, taking this picture.]